Many schools in the northern hemisphere will resume in-person classes in the coming weeks after over a year of intermittent closures - despite the continued presence and uncertain evolution of the COVID-19 virus. Other schools will opt for hybrid teaching and learning. Whichever modality they choose, the reopening of schools that had been closed because of COVID-19 continues to raise many questions for school leaders. They need to put the school community’s safety and health first. At the same time, they have to ensure that schools’ front-line workers – teachers and education support staff – have the help, protection and tools they need to resume work. Teachers have played a key role during school closures by ensuring that learning can continue and by keeping in touch with students and their families. Their role during school reopening will be just as important.

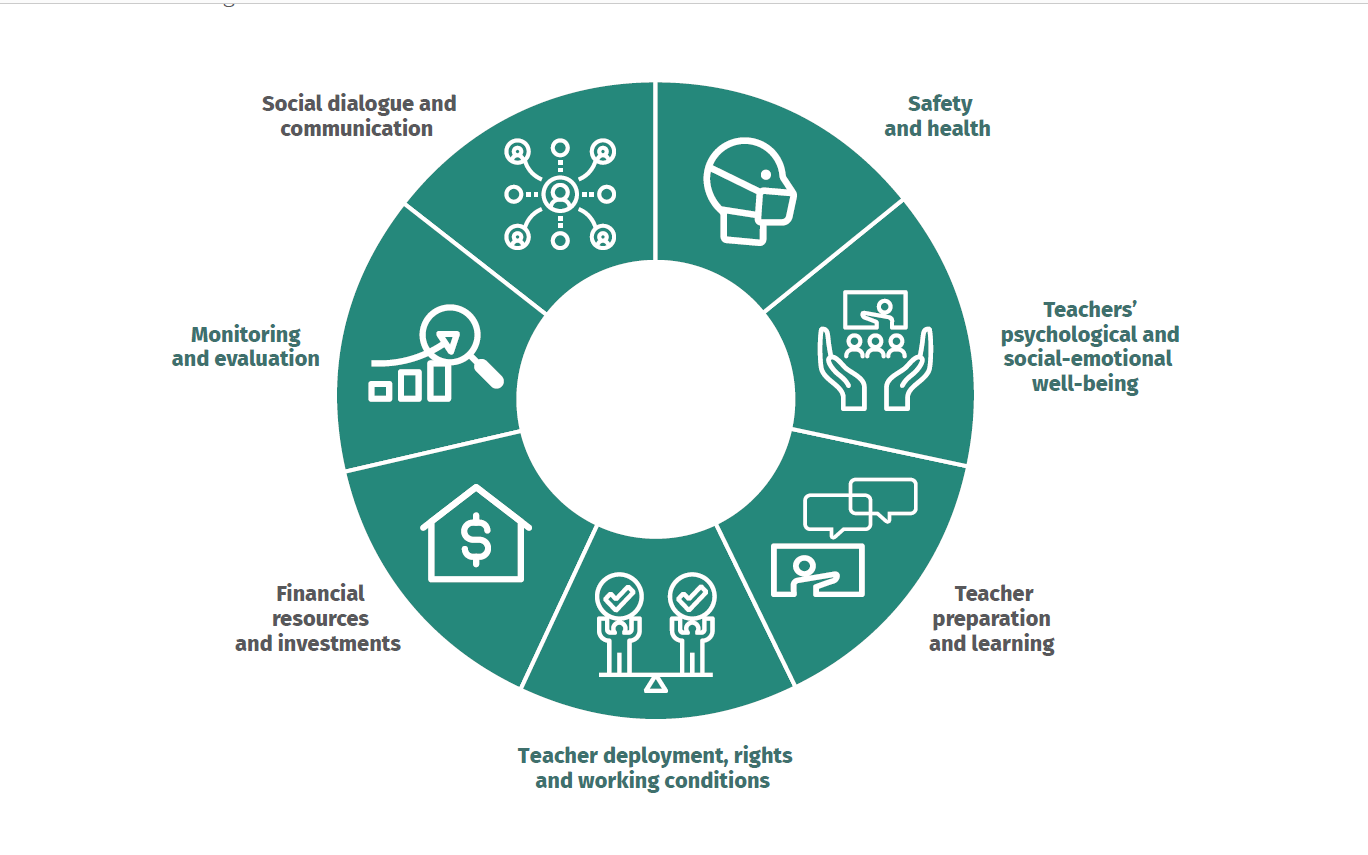

Last year, UNESCO, the Teacher Task Force and the International Labour Organization released a toolkit to help school leaders support and protect teachers and education support staff in the return to school. The toolkit complements the joint Framework for Reopening Schools and the Task Force's policy guidance. It breaks down the seven dimensions in the policy guidance into a series of actionable guiding questions and tips. While many education systems have already been closed and reopened several times over the past year, the dimensions on supporting and protecting teachers and students remain relevant. These include how to support teachers’ health, safety and well-being, how to foster dialogue with teachers and the community, and how to ensure learning resumes.

Download the Toolkit in English, French, Spanish and Arabic.

Seven dimensions to support teachers and staff as schools reopen:

The toolkit recognizes the importance of local context. In many countries the pandemic is still evolving daily. Local decisions about when to reopen schools will be determined by a broad range of considerations; what is right for one school may not be right for another. In all contexts, school leaders will need to set priorities and recognize that trade-offs may be needed.

The toolkit shows us that school leaders will need to think about key issues in relation to teachers and education support staff as they adapt national directives to plan to reopen their schools.

- The importance of consultation and communication

Teachers, school staff and their representative organizations should be actively involved in setting out policies and plans for school reopening, including occupational safety and health measures to protect personnel. Communication with teachers, learners and education support staff about reopening can ensure clarity about expectations and highlight their role in the success of safe, inclusive return-to-school efforts, including overall well-being, and the teaching and learning recovery process.

As decisions to reopen schools are made by central authorities, it will be important to communicate early, clearly and regularly with parents and school communities to understand their concerns and build support for plans to reopen. Parents will want to know what safeguards have been put in place to minimize health risks. They will also need to hear about the school’s ongoing commitment to key educational principles and goals. As teachers are often the first point of contact with parents, they will need to be prepared to ensure everyone is informed continually.

- Reassuring teachers and school staff about their health, safety and rights

Concern for the well-being of teachers, support staff and students is at the heart of decision-making. It is important to balance the desire to return to school with consideration of the risks to (and needs of) teachers, support staff and learners, so that the needs of the most vulnerable members of the school community are met.

School-level responses may include ongoing psychological and socio-emotional assessment, and support for teachers and learners. School leaders and teachers should be free to address their own needs, exercise self-care and manage their own stress. School leaders can help teachers develop stress management skills and coping mechanisms, so they can teach effectively and provide much-needed psychosocial support to learners. It is also critical to understand that schools are a workplace and that it is more vital than ever to respect the rights and conditions of the people who work there.

“Before schools reopened, the teachers were worried about resuming work and contracting the virus, as were the parents. We had no WASH facilities, no masks and large classes. Discussions with health staff would have helped us a lot. It would also have been reassuring to have psychologists in schools for psychosocial care. In the end, we were able to obtain sufficient sanitation and masks from an international NGO, and only one grade returned to school to prepare for exams. The classes were split in two", stated a Primary school principal from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

- Using teachers’ expertise in the new classroom environment

In most contexts, when children return to classrooms it will not be business as usual. In some cases, only some students will be present, or there will be double shifts. Lesson plans, assessment and overall curricula will be adapted, and remedial lessons will need to be developed and deployed.

School leaders need to ensure teachers are empowered to make decisions about teaching and learning. They can work with teachers to adjust curricula and assessment based on revised school calendars and instructions from central authorities. School leaders should also support teachers to reorganize classrooms to allow for accelerated learning and remedial responses, while adhering to regulations on physical distancing.

Teachers’ key role in recognizing learning gaps and formulating pedagogical responses remains critical. This is especially true for vulnerable groups, including low-income families, girls, those with special needs or disabilities, ethnic or cultural minorities and those living in remote rural areas with no access to distance education.

To manage the return to school, it is important for teachers and education support staff to receive adequate professional preparation to assume their responsibilities and meet expectations. Training, peer-to-peer learning and collaboration with other teachers, both within the school and more broadly, will be critical. Such support is particularly important where additional strain may be placed on teachers’ time if they are required to conduct both face-to-face and distance education.

Education recovery will require investments to ensure that a generation of learners is not lost. Which is why the Teacher Task Force is urgently calling for greater investment in teachers and teaching. Read the Call for Greater Investment

Download the Toolkit in English, French, Spanish and Arabic.

See also the Guidelines for national authorities in Arabic, English, French and Spanish.

Photo credit: MIA Studio/Shutterstock.com