This blog was written by Mark Bray, UNESCO Chair Professor in Comparative Education at the University of Hong Kong, and Director of the Centre for International Research in Supplementary Tutoring (CIRIST) at East China Normal University (ECNU). It reflects the author's opinions, which are not necessarily those of the TTF.

Shadow education and implications for policy

The theme of non-state actors in education, which has huge importance throughout the world, will be the focus for the 2021 edition of UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report. A key dimension includes the private supplementary tutoring undertaken by public school teachers. In the literature, private supplementary tutoring is commonly called shadow education. The metaphor is used because as the curriculum changes in schools, so it changes in the shadow; and as the school system expands, so does the shadow.

Shadow education has long been visible in East Asia, and is now a global phenomenon. While shadow education has received much attention in Egypt and some other parts of North Africa, it is neglected in Sub-Saharan Africa. This article draws on a book entitled Shadow Education in Africa (available in English and in French), the genesis of which was a background paper for UNESCO’s GEM Report.

How widespread is shadow education?

Reliable statistics are scarce, and one message of the book is that better data are urgently needed. Nevertheless, the following statistics shed some light on the prevalence of shadow education.

- In Angola 94% of surveyed students in Grades 11 and 12 (2015) were receiving or had received tutoring at some time.

- In Burkina Faso, 46% of surveyed upper primary students (2014/15) were receiving tutoring at the time of the study.

- In Egypt, 91% of Grade 12 respondents (2014) indicated that they were either currently receiving tutoring or, if they had graduated, had done so before completion.

Other sources show trends over time (Table 1), with significant growth that has likely continued. Some of this tutoring is provided by commercial entrepreneurs who operate tutorial centres, and some is provided by university students and others who operate informally. In Africa, most tutoring is provided by in-service teachers taking additional employment as part-time occupations.

Table 1: Enrolment Rates in Private Tutoring, Grade 6, 2007 and 2013 (%)

Source: SACMEQ National Reports.

What issues arise when teachers are also tutors?

Private supplementary tutoring can be beneficial. It can help slow learners to catch up with their peers, and can strengthen countries’ overall human capital. It also provides extra income for teachers, perhaps helping to retain them in the profession. In many African countries, high proportions of school personnel are contract teachers who commonly have relatively low salaries. Even teachers forming part of the civil service may feel that their salaries are inadequate to meet all family needs.

Source: http://gem-report-2017.unesco.org/en/countonme

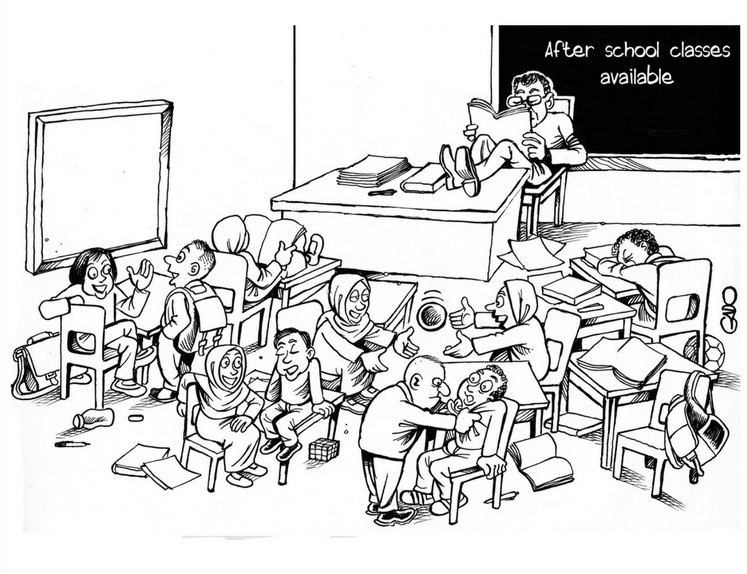

Yet when teachers are also tutors, several problematic issues arise. One is that the teachers may neglect their regular teaching duties in order to devote time and energy to their private lessons. Especially problematic situations arise when teachers tutor the students for whom they are already responsible in mainstream schooling. For example, the danger arises of deliberate reduction of attention during regular lessons in order to promote demand for private tutoring. Dangers also arise of discrimination in the classroom, when teachers openly or covertly favour the students receiving supplementary lessons from them.

What are the policy implications?

The first need is for the topic to be taken out of the shadows – to be discussed not only by Ministry of Education personnel but also by professional bodies at sub-national, school and community levels. Some governments, e.g. in Egypt, Eritrea, The Gambia and Kenya, explicitly prohibit private tutoring by serving teachers. Other governments, for example in Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, permit such tutoring but prohibit it on school premises. Another category, exemplified by Mozambique, permits private tutoring with official permission but explicitly forbids teachers from tutoring their existing students.

Yet many of these policies exist more on paper than in practice. Governments do not have strong machinery to enforce prohibitions, especially when many actors are sympathetic to the status quo. Thus, even parents may exert pressures on teachers and schools since they want their children to perform well in a competitive environment. Parents frequently feel their children’s teachers know the children best and can therefore provide better support than tutorial centres or other providers.

This situation underlines the need to accompany policies with practical measures to ensure better regulation. Yet sometimes governments feel that the mechanisms to monitor and regulate the practice are inadequate, leading to the development of laissez-faire policies that do little to regulate the problem.

What about the school level?

Even if governments turn a blind eye to the problem, schools can issue their own policies and monitor patterns to avoid ethical malpractice. Schools can help explain the issues to parents, and support finding alternatives to support their children’s needs. School-level policies may be especially effective, since teachers and parents are well known to one another resulting in that guidelines and sanctions are more likely to be meaningful and effective. Nevertheless, it must be recognised that sometimes schools are complicit in encouraging tutoring in order to generate extra revenue for institutional and/or personal uses.

Learning from each other

Some people assume that if the quality of schooling is improved, then shadow education will disappear by itself. Global trends however show the opposite. The East Asian countries that have much shadow education also have strong education systems. Rather, globalisation has increased pressures on families to compete resulting in that shadow education is on the rise in many European and high-income countries. Thus also in Denmark and Finland, which are renowned for the quality of their schooling, the expansion of shadow education is visible. This trend suggests that shadow education is a concern not only in countries where it is already strong but also in those where it is not so strong. In the latter case, policy-makers have the opportunity to shape the sector before it becomes engrained in cultures..

Further, the fact that large-scale shadow education has been evident for a longer time in Asia, may bring insights for other parts of the world. One regional study on this theme is entitled Regulating private tutoring for public good.