This teacher is using mindfulness and WhatsApp to keep girls in Bangladesh learning despite school closures

While schools in most countries have now reopened their doors after the Covid-19 hiatus, in Bangladesh the government recently decided to extend the shutdown of educational institutions. Pupils have been out of school since March 17.

For teachers, the extended period out of school is both a challenge – to keep students engaged and learning – and an opportunity to rethink how education should be delivered.

Reimagining teaching

Sharmistha Deb is a teacher whose experience of supporting her female fourth-grade students remotely has led her to start a project developing new content on social-emotional learning.

“Research suggests that such learning can help reduce anxiety, suicide, substance abuse, depression, and impulsive behaviour in children,” says Sharmistha, “while increasing test scores, attendance, and social behaviours such as kindness, personal awareness and empathy.”

Lockdown has challenged the wellbeing of many children in Bangladesh. One assessment, conducted in May, found that over half were not taking part in online classes or watching the televised lessons aimed at families without internet access.

Asif Saleh, the executive director of BRAC – an NGO that provides a wide range of services across Bangladesh – has raised concerns about an increase in child marriages in rural areas, while urban areas are seeing more problems with youth crime and drugs.

Learning from previous crises

These reports mirror experiences in Africa during the Ebola crisis, according to UNESCO’s report ‘Addressing the gender dimensions of COVID-related school closures’: Ebola-related school closures “led to increases in early and forced marriages, transactional sex to cover basic needs and sexual abuse, while adolescent pregnancy increased by up to 65% in some communities”.

Sharmistha, a Fellow of the Teach for Bangladesh Fellowship programme, which aims to reduce educational disparities and build the long term leadership skills of educators, wanted the 33 girls in her class to feel connected and important while their school was closed. She uses a range of apps to keep in touch with them – Imo, Viber, WhatsApp and Facebook, as well as phone calls – and check on their mental health.

She found they were experiencing a wide range of psychological impacts due to being isolated from their friends and having to adjust to radically different daily routines, often with more responsibilities for looking after family members. Lockdown increased the financial insecurity of their households, which had already put some of the girls at risk of exploitation and child marriage.

Mental health mentoring

Sharmistha talks to the girls about five ways to boost mental health – prayer, healthy food, meditation, exercise and sleep. These conversations have deepened Sharmistha’s belief that teachers need to support students with their emotional wellbeing, help them to deal with anxiety and develop their self-confidence so they in turn can support their families and communities.

“Students may need additional psychological and socio-emotional support” because of lockdown, notes Supporting teachers in back-to-school efforts: A toolkit for school leaders, a recent publication by UNESCO, the Teacher Task Force and ILO. “A whole new set of vulnerabilities could have reared up during school closures, including disruption of vital safety nets such as school meals or exposure to other trauma in ‘at-risk’ households.”

Among the toolkit’s suggestions is “providing checklists for teachers to assess learners’ behaviour and reactions in relation to stress and anxiety”, and making sure teachers know how to report suspicions of abuse.

Building back equal: Girls back to school guide, calls for “professional development for teachers, school management and other education sector staff to identify and support girls who are struggling psychologically.”

Getting girls back to school

There is the challenge of getting girls back to school, after months away and amid continuing fear of the pandemic. Erum Mariam, the executive director of BRAC Institute of Educational Development, says frontline workers need to “give these families psychosocial assistance and to convince parents to send their children back to school… We cannot work under the assumption that once schools open, children will return.”

After the Ebola crisis there were “increases in school drop-outs among girls when schools reopened”.

Sharmistha is already planning how to integrate social-emotional learning into her lessons, with activities on mindfulness, self-control, relationship building, anger management, coping with stress, empathy, conflict resolution and social sensitivity, and identifying the early signs of mental illness.

“We need to develop social-emotional learning strategies that actually work as proactive initiatives for preventing mental illness,” she explains.

*

This blog is part of a series of stories addressing the importance of the work of, and the challenges faced by teachers in the lead up to the 2020 World Teachers’ Day celebrations.

*

Cover photo credit: Teach For Bangladesh

These 3 charts show there is still work to do to reach gender equality in the classroom

Education ministries are working to create inclusive and equitable classrooms in pursuit of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4). A key part of this is gender equality (SDG 5). These three charts give an insight into the complex picture of gender in teaching.

Chart 1: Two thirds of the world’s teaching workforce is female

The proportion of women in teaching has grown in the past few decades, and today women make up about two-thirds of the world’s teaching workforce (64 per cent). However, to say that women are dominant in the profession would be an oversimplification; the proportion of female teachers varies with factors such as region, subject, seniority, and education level.

For instance, data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics show that globally women make up a decreasing proportion of the teaching workforce. While 94 percent of pre-primary educators globally are women, this falls to 66 per cent in primary education, 54 per cent in secondary education and 43 per cent in tertiary education.

In high-income countries, teaching is a predominantly female profession with post-secondary education being the exception. In some parts of Europe, Asia-Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, this gender divide is extreme as women make up more than 90 per cent of primary and secondary school teachers.

While women are better represented in many regions, in sub-Saharan Africa, they are underrepresented in primary, secondary, and tertiary teaching standing at 45 per cent, 30 per cent and 24 per cent, respectively. The are the majority in pre-primary education at 80 per cent of all teachers.

Chart 2: In parts of Africa females in secondary education represent fewer than 30% of teachers

Many low-income countries have the opposite imbalance.

This map shows poor female representation in secondary education in Africa. Most countries with very low proportions of women in teaching are found in the Sub-Saharan African region. In Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Chad, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Eritrea, DR Congo, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Sierra Leone and South Sudan, for example, fewer than 30 per cent of secondary school teachers are women.

There has been a gradual movement towards gender parity in education systems in lower income regions. And efforts appear to be working. Since 2000, the proportion of women primary school teachers increased from 38 to 53 per cent in Southern Asia and from 42 per cent to 46 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa.

Chart 3: Male and female teachers are almost equal in terms of having achieved the minimum qualifications to teach at each level

On a global scale, male and female teachers are near equal with regards to earning the necessary qualifications to teach at all levels. Yet there are significant gender disparities in a number of areas.

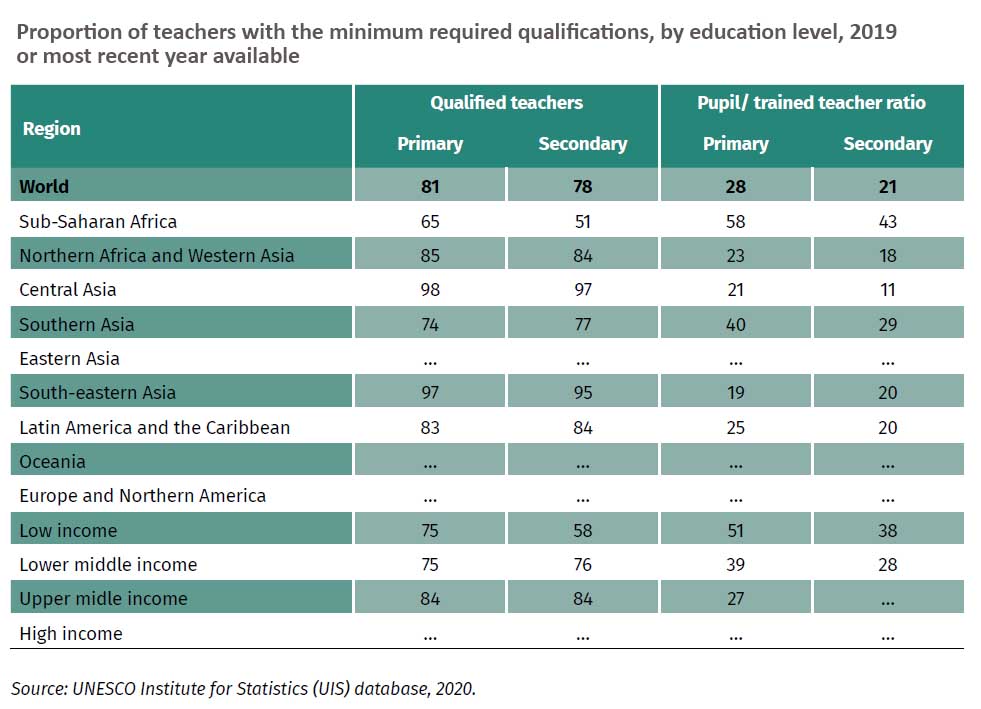

For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, where just 65 per cent of primary and 51 per cent of secondary school teachers have the minimum required qualifications to teach, men comprise a slightly larger proportion of primary school teachers with the minimum required qualifications.

In some countries in sub-Saharan Africa however, female primary school teachers are more likely to have earned their qualifications than their male colleagues.

Yet despite being more likely to be qualified, women teachers still face inequality when entering the workforce.

In some cases, this disparity is particularly significant. Around 73 per cent of female primary school teachers in Sierra Leone had the minimum required qualifications compared with 59 per cent of male teachers.

The overrepresentation of men in teaching across sub-Saharan Africa may suggest that a lack of qualifications presents a greater barrier to women entering teaching than men with the same qualifications in some countries.

More support for women teachers needed

Teachers are role models, so it is vital for the teaching workforce to reflect the diversity of their students. Studies suggest that being taught by women may be correlated with improved academic performance and continued education among girls, while having no negative impact on boys. Working towards a teaching workforce in which women and men are equally empowered is key to ensuring inclusive education for all.

There is still some way to go before gender equality is reached in teaching. Efforts to reach gender equality should not be limited to encouraging more men to enter pre-primary and primary teaching, but should also include supporting women teaching at higher levels and in leadership positions.

*

This blog is part of a series of stories addressing the importance of the work of, and the challenges faced by teachers in the lead up to the 2020 World Teachers’ Day celebrations.

*

Consult the Gender in Teaching - A key dimension of inclusion infographic published by UNESCO and the International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030.

*

Cover photo credit: Sandra Calligaro

Regional Virtual Meeting for Arab States - Teachers Leading in crisis, reimagining the future

The International Task force on Teachers for Education 2030 (TTF) in collaboration with UNESCO Beirut and UNICEF Regional Offices will host a Regional Virtual Meeting for Arab States on 8 October at 10:00h-11:30 (Paris time GTM +2).

Following from the Regional Meetings initiated in May/June of 2020 on distance teaching and the return to school, the TTF, with member organizations and partners is organizing a new series of discussions to coincide with the WTD celebration. These will build on the initial dialogue while also exploring the topic of teacher leadership and its key role in developing effective solutions to address challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and building back resilient education systems.

In particular, the regional meetings will provide a forum to:

- Share examples of leadership that emerged, were implemented or are planned during different phases of the pandemic including the transition to remote teaching and the return to school;

- Identify the different systemic or policy level enabling factors that were conducive to foster effective leadership amongst school leaders and teachers at the classroom-, school- and community-levels;

- Identify challenges that need to be addressed to ensure leadership can be enhanced and teachers can take the lead on different dimensions of teaching and learning;

- Discuss different tools available to support teacher leadership, including the new TTF Toolkit for Reopening Schools, and TTF Knowledge Platform.

Some of the main questions to be covered will include:

- What government interventions were implemented or are planned to strengthen leadership capacity of school leaders and teachers to ensure the continuity of learning in the use of distance education and the return to school (if applicable) at the classroom-, school-, and community-levels?

- Given the lack of time to prepare for school closures in most countries, what examples of leadership decisions and actions emerged to ensure the continuity of learning at the micro-(classroom), meso-(school) and macro- (community) levels?

- What forms of social dialogue were conducted or are planned within a strong teacher leadership orientation to ensure the voices of teachers are included in planning?

- What enabling factors and challenges currently exist to foster a leadership mindset?

The meeting is open to TTF member countries and organizations as well as non-members. TTF focal points, representatives of Ministries of Education, and other relevant education stakeholders working on teachers’ issues in the region are invited to join the meeting.

- Read the Concept Note

-

Register her

-

Watch the video (in Arabic)

Teaching K-12 Science and Engineering During a Crisis

To improve the state of education around the world we need to support teachers. This is how

This is a blog drawing on the conclusions of the 2020 World Teachers' Day fact sheet published by the International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030, UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the Global Education Monitoring Report.

COVID-19 has closed schools around the world, separating students from their teachers and classmates. Even as many teachers attempt a return to some normality, reopening schools and reintegrating students brings its own challenges.

This World Teachers’ Day (October 5th), we are taking stock of some of the challenges facing teachers and identifying what needs to be done to help them provide quality education for all.

The world needs more teachers

‘Quality education’, the fourth UN Sustainable Development Goal, has never been more important. For all the disruption, the pandemic is also an opportunity. By focusing on educating and energising younger generations, societies can plan a route out of COVID-19 that leads to a better world.

For this we need more qualified teachers. There are already 28 million more teachers worldwide than there were 20 years ago, but this does not meet the demand for the 69 million teachers previously estimated to ensure universal primary and secondary education by 2030. The need is greater in disadvantaged regions. For example, 70% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa have teacher shortages at primary level, with an average of 58 students to every qualified teacher. Compare this with South-eastern Asia where the average ratio is only 19 students to every teacher.

Levels of teacher training also differ greatly between global regions: 65% of primary teachers in sub-Saharan Africa have the minimum qualifications required trained, compared with 98% in Central Asia.

It is a complex conundrum: education is the best way for disadvantaged societies to redress global inequalities, but they are fundamentally handicapped, with neither the capacity nor teacher training to give every student the support they need.

Who teaches the teachers?

There are some concrete proposals that aim to increase the level of support teachers receive. The African Union, for example, has developed universal standards for teacher qualifications that will ensure all teachers are equipped with the knowledge, skills and values they need. This means those teachers will be better prepared when they enter the classroom, and this, coupled with wider recruitment to decrease classroom sizes, can greatly improve the quality of education systems in the region.

COVID-19 has forced a transition to remote and online learning. Teachers therefore urgently need better training in information and communication technology (ICT). Yet research shows that only 43% of teachers in OECD countries feel prepared to use ICT to deliver lessons. Help is coming, but again the pandemic shines a light on global inequality as too many homes in low-income countries lack the devices and connectivity to learn online. Teacher in low income countries also struggle given that only 41% of them receive teachers practical ICT guidance, compared with 71% in high-income countries.

Look to the leaders

Leadership training can mitigate the worst disparities of COVID-19, empowering individual teachers to lead their colleagues through this difficult time.

Strong leaders create a culture of trust in schools, instilling a collective sense of responsibility, and offering support and recognition. For example, Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) are forums where teachers can support one another’s training and development. In Rwanda, 843 school leaders, having completed a diploma in school leadership, are using PLCs to share the benefit of their training with colleagues. In South Africa, school leaders are encouraged to set up PLCs and use them to induct novice teachers into the profession, giving them the confidence to take responsibility for their own professional development. And in Ecuador, 287 school leaders participate in PLCs to exchange best practices and organise themselves into a supportive network.

What else do teachers need?

Better training and strong leadership within schools will benefit global education systems for years to come. But another issue made more urgent by the pandemic is inclusivity. As students return to school, the ability of teachers to promote an inclusive environment is a vital skill to mitigate disruption and ensure students aren’t excluded from learning.

61% of countries from a recent survey claim to train their teachers on inclusivity skills, but very few guarantee such training in their policies or laws. However, the pandemic has already done enough to distance teachers from their students and students from each other. With many schools still observing physical distancing to slow the spread of the virus, specific training in inclusive teaching is necessary to ensure a cohesive and effective learning environment.

Much work done, much still to do

Teachers must be given guidance and professional development opportunities to ensure they feel equipped to hold their classrooms together, physically or virtually. In many parts of the world, this is sorely lacking.

Work is underway to improve the situation. New standards are being set, training is being implemented, and everywhere strong leaders are creating inclusive, supportive learning environments. For true progress to be made however, governments must listen to teachers and teacher unions. Real change can only happen if teachers' voices are heard. Teachers and policymakers need to navigate this new world together.

Consult the 2020 World Teachers' Day fact sheet published by the International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030, UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the Global Education Monitoring Report.

This blog is part of a series of stories addressing the importance of the work of, and the challenges faced by teachers in the lead up to this year’s World Teachers’ Day celebrations.

*

Cover photo credit: GPE/Kelley Lynch