Chris Henderson, Geneva Graduate Institute and NORRAG.

Teachers in crisis and emergency contexts regularly come under attack while carrying out their fundamental work, which jeopardises many teachers’ strong sense of resilience, purpose, and well-being.

Sadly, too many teachers around the world from all regions continue to be at risk. Since 24 February 2022, more than 3,500 educational institutions have reportedly been damaged or destroyed by bombing and shelling in Ukraine, according to the country’s Ministry of Education and Science (MoES); other reports also cite attacks on teachers themselves (GCPEA, 2023).

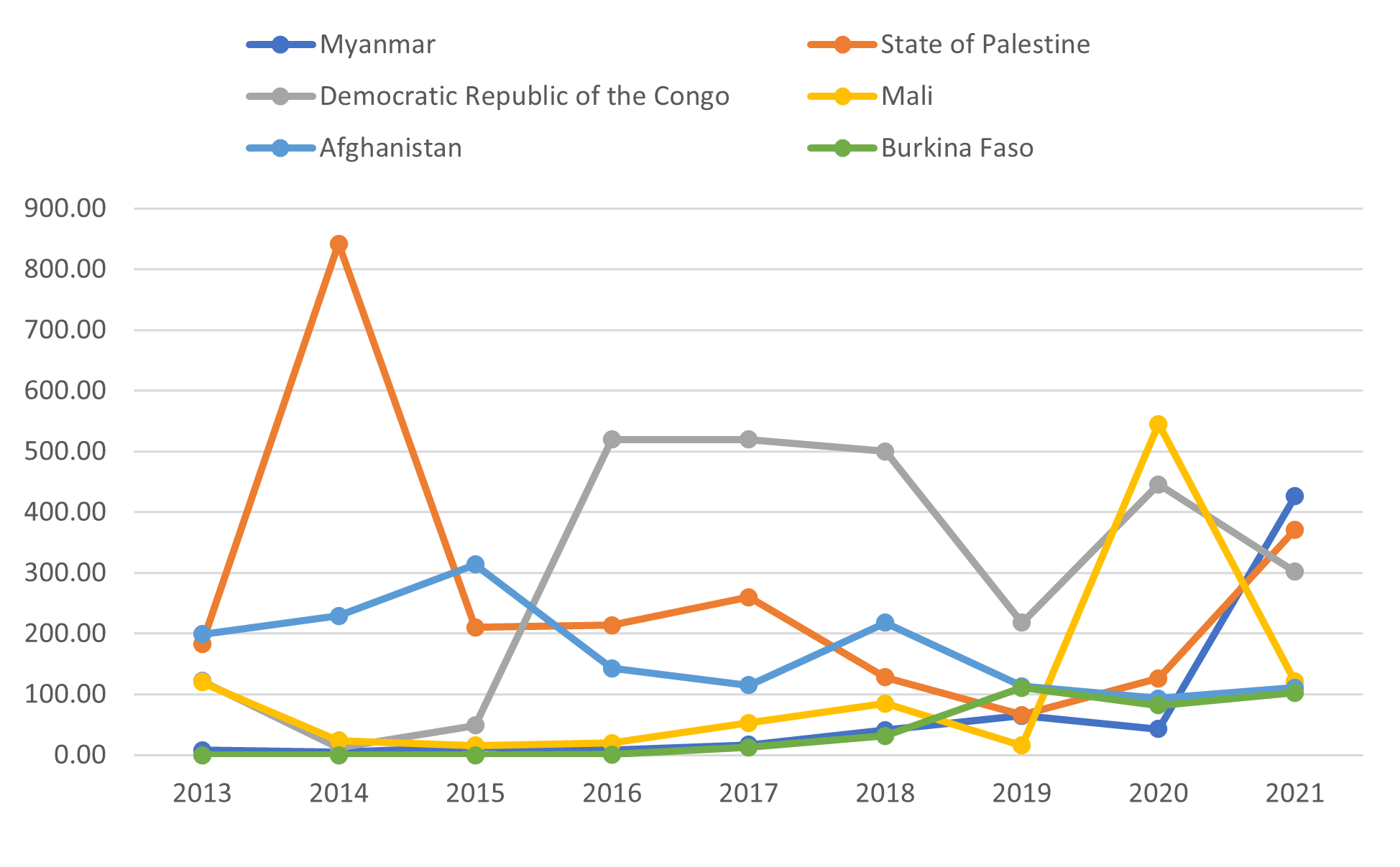

In order to monitor crises, globally, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) tracks data on the number of attacks on students, personnel and institutions representing Sustainable Development Target 4.a.3. Currently, there are data available for 101 countries between 2013 and 2021. Figure 1 shows the five countries experiencing the most attacks on students, personnel and institutions . In 2021, teachers experienced the greatest risk in Myanmar with 426 attacks. The State of Palestine experienced 371 attacks, the Democratic Republic of the Congo suffered 302, and Afghanistan, Burkina Faso and Mali each accounted for more than 100 attacks. As seen in Figure 1, the number of attacks in Myanmar and the State of Palestine are rising at a rapid rate, meaning the risks that teachers face each day are rising, too.

Number of attacks on students, personnel and institutions, 2013 – 2021

Teachers are denied the safety and dignity that they deserve

In some contexts, teachers are threatened, abducted, or killed because they represent the state or it is due their membership in teachers’ unions. Teachers also suffer sexual violence during or after attacks on schools by armed groups. In other conflicts, teachers are killed or injured by explosive weapons on their way to or from school or in violent clashes between armed groups.

Where schools and universities are used as bases and barracks, these facilities can be targeted by opposing force air strikes or ground attacks, which also places teachers at considerable risk. Globally, incidents of military use of schools and universities more than doubled between 2020 and 2021.

Teachers are targets in many places

The effects of these realities on teachers and on the children and adolescents they teach are profound. For example, in Colombia, which witnessed 83 attacks in 2021 (UIS, 2023), teachers report that threats and acts of violence shift the quality of their teaching practices. Some teachers also report that violence alters their sense of trust and the authenticity of their engagement with pupils and their families. Some teachers further reported they avoid teaching certain subjects due to the violence that state-sanctioned histories can incite.

Some teachers who actively engage in peacebuilding efforts to curb the recruitment of their pupils into armed forces have also been targeted by paramilitary groups. In Colombia’s El Salado community, for example, all 25 teachers working at one school received messages from a paramilitary group threatening to extreme violence against the teachers themselves. Incidents like these are not isolated.

In Afghanistan, where the Taliban has re-ascended, there are reports of numerous education leaders being threatened, arrested, or killed for promoting girls’ education. Elsewhere, armed extremists like Boko Haram in Nigeria oppose western-oriented education and have threatened, killed, or abducted teachers to prevent them from teaching national curricula (GCPEA, 2022). Teachers share that their morale is deeply affected by attacks on their colleagues, with the daily insecurity that they experience making it almost impossible to teach.

In Syria, GCPEA describes how resistance forces target and forcibly conscript teachers. In Myanmar, teachers aligned with the resistance National Unity Government (NUG), which is in opposition to the current government, have been targeted. Over 40 teachers were abducted and killed in 2021 alone.

Violence has a negative impact on teacher recruitment and retention

Ring & West (2015) note how trauma from violent conflict and forced displacement compromises teachers’ capability to fulfil the functions of their roles. As teachers navigate complex stressors in their own lives, overcrowded classrooms of conflict-affected children and adolescents, who are in need of intensive psychosocial and socio-emotional support, leave teachers feeling unprepared and overstretched. This lowers teachers’ sense of self-efficacy – the belief that their actions have an influence on outcomes – which is a key predictor of teachers’ motivation to teach. In sum, violence and trauma influences teacher attrition and exacerbates teacher shortages where teachers are needed most.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo Wolf et al., (2014) report on the effects of poor teacher well-being on education system quality . As one of the first empirical studies to conceptualise and measure teacher well-being in a crisis context, their study applies the concept ‘cumulative risk’ to describe the adverse conditions and many stressors that affect teachers’ work and well-being. Their study shows a statistically significant and negative relationship between cumulative risk and teachers’ motivation to teach, meaning that the more risk teachers experience in their work, the less motivated they are to remain in the teaching profession.

Similarly, their findings demonstrate a significant and positive relationship between cumulative risk and burnout, whereby as a teachers’ exposure to risk rises, the more likely they are to report burnout. Thus, for teachers to be able to function to their fullest capacity, free from physical and psychological harm, teacher well-being and the prioritisation of teachers’ protection must be at the forefront of recruitment and retention-focused policy and funding.

We must act now to increase the appeal of the profession

These studies, among others, represent a crisis within a crisis. In contexts where schools and teachers are vulnerable to attack, and where inadequate pay, non-existent psychosocial support, and poor professional development compounds the violence that teachers face, the work of teaching is perceived as a risk in and of itself. Symbolic of this reality, in Kenya’s Dadaab Refugee Camp only 18 per cent of refugee teachers want to be teaching in three years’ time and just four per cent of host-community teachers aspire for the same.

Our failure to protect teachers from attack exacerbates the global teacher shortage. It undermines the attractiveness of the profession and forces many to abandon their roles. As World Teachers’ Day[1] approaches on 5 October, our advocacy for quality education in crisis contexts must prioritise teachers’ basic human right to a safe and healthy working environment and the status and dignity that should be afforded to all members of the profession.

Useful links:

- Crisis-sensitive Teacher Policy and Planning: Module on the Teacher Policy Development Guide

- Official World Teachers’ Day page

Photo: Nan Maw Maw Kyi. Teacher. Myanmar. © UNICEF/UN061811/Brown